In this new documentary, Nigel Konstam provides an alternative view of the sculpting techniques of the ancient Greeks, with a focus on the controversial view that they employed plaster and wax to make moulds taken from living people - known as "life casting".

This practice is highly frowned upon in art and art history circles, but Konstam aims to prove that this is a modern taboo, and certainly not above the most legendary of ancient artists. More videos by NK.

If you have any questions about this video, there is a dedicated Facebook group, or you can contact Konstam directly.

Introduction

As I have crammed too many ideas into the video of “A Sculptors Perspective” (18 minutes) I have written this Introduction to avoid confusion.

1. In introducing myself I include a demo of how flexible wax is: changing the manikin into a number of small and varied bronzes, all came from the same mould.

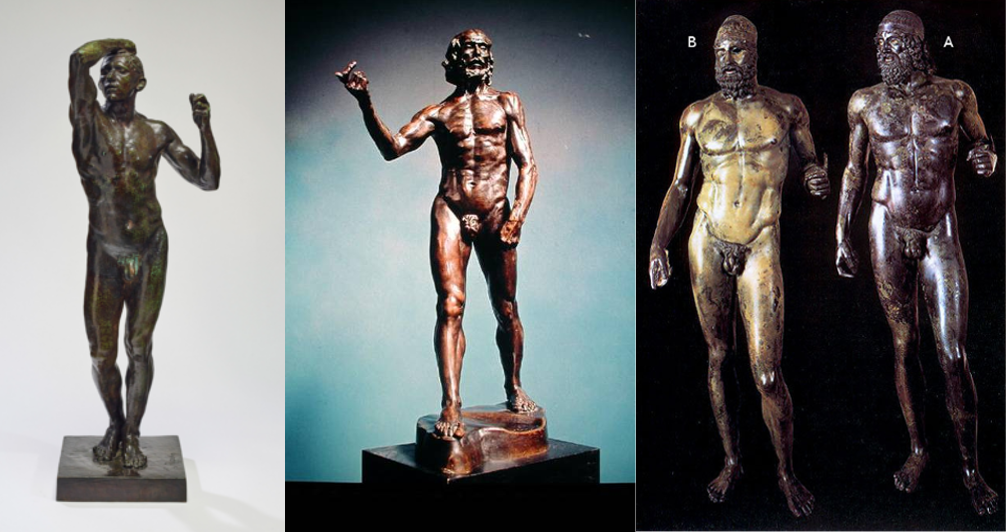

2. There is plenty of visual evidence of Life-Casting on the surface of “The Bronzes of Riace”. If one compares the modelling of the hand, wrist and arm of Figure A with the same area in a Rodin - for instance in “The Age of Bronze” or the figure of “St.John the Baptist” both of which are modelled very closely on the live model by the world’s greatest modeller, the difference is obvious. However, the clear proof of the use of life-casting is in the soles of the feet of “The Bronzes of Riace” (see The Oxford Journal of Archaeology 2004) and those of The Apollo of Piombino.

3. This argument is taken beyond bronzes by suggesting that the Greeks also used the hollow wax taken from the plaster negative of a life-cast, cut up and reassembled, to create their compositions in marble at Olympia, on the Parthenon (Dionysos) and by many Greeks thereafter.

4. Olympia is considered a miraculous transformation from the more primitive archaic style. The miracle can be explained by life-casting. There is also good evidence of the same on the Parthenon. The figure of Dionysos is the best example insofar as the joint between his chest and the torso below has been copied from the wax original so perfectly by the artisan carver that it no longer has anything to do with the anatomy at that juncture. It looks very much more like a rough joint having been cut in the hollow wax with what a dressmaker would call a dart to make the figure’s movement; bent as we see it rather than standing upright as I presume the original was formed.

5. The necessity of a chimney to speedily melt large quantities of bronze shows the current interpretation of “The Foundry Cup” seriously under estimates the amount of heat required to melt the necessary bronze for the gigantic statues we know existed in Athens. (see The Oxford Journal of Archaeology 2002)

6. The need to replace the sculptures on the west pediment is explained by the chimney whose smoke damaged the west facade. This is clearly shown in an early photograph of the Parthenon (blackened by smoke from 432 BC onwards).

7. The figure of Illysos (Roman) is contrasted with that of Dionysos (Greek, east pediment) because it is the best preserved on the west pediment and is similar in movement. Dionysos is genuine Greek and the difference in quality, particularly in that area of the stomach, is obvious and attributable to the different times of production. To everyone’s surprise the Roman is artistically superior to the Greek; art history has consistently told us the reverse.

8. The same is true of the comparison of the horses: Selene (Roman) and Helios (Greek).

9. “Michelangelo's Models” introduces a related idea: in my view art historians have held a mistaken view for centuries, of the role of the imagination in art. The art we most admire is the result of observation - interpreted by comparison with remembered experience. Invention is much vaunted today but to communicate we need a common language, the natural world provides such a visual language through common experience. Novelty inventions are unlikely to help in this communication.

10. Art historians normally much prefer invention to observation; in their view observation is okay for apprentices, or the common run of artists but not for such masters as Michelangelo, Rembrandt or the Greeks, who work imaginatively, or so they affirm. An amusing story to demonstrate the artist’s view:- Rodin, skeptical of Blake’s art was told that it was based on genuine visions, Rodin replied “he should have looked not once but many times”. Alas, visions are fleeting, even the great feed their imagination with reality, preferably immobile reality. It is easier to observe and measure that way. Until art history accepts this common knowledge among artists, we will go on losing important works – and equally important, the truth about the means of their production. This persistent historical error has created a destructive gulf between artists of the past and those of today.

Also available in Italian - Disponibile anche in italiano

Compare the work of the ancient Greeks (Riace bronzes, right) to the work of Rodin (Age of Bronze and John the Baptist, left and centre) from over 2000 later