The Mirrors

I rely on the evidence of mirrors to raise what I believe to be a very credible hypothesis to the level of proof: a proof that should convince the most rigorous sceptic or stand up in any court of law. Rembrandt's use of mirrors produces relationships which are complex and varied; yet the images and the mirror-images can be shown to fit together like the pieces of a three dimensional puzzle. It seems impossible to me that the drawings discussed in this chapter could have been produced by any other means - let those with doubts suggest alternatives.

Please differentiate between mirror images which are a reversal of a different point of view of a three dimensional object and a print image which is a straight reversal between the drawn image on the plate and then reversed in an etching. The present chairman of the Rembrandt Research Project (Prof.E.Van der Wetering) fails to understand the difference!

a) Reality and Reflection

The drawings of mummers and musicians argue against the theory that Rembrandt had a photographic or eidetic memory. Mummers & Musicians The drawings are examples of Rembrandt's most direct use of mirrors, where reality and reflection appear together in the same drawing. Further examples are offered here, in Pls. 17a,b 18a,b, and 19a,b. Still further examples in which the same procedure has very probably been used are listed in Appendix 1-A.

In the drawing called Two Orientals Disputing (pls.17a,b) the strong character of the pose is readily recognisable in both figures. The drawing might better have been entitled An Oriental Disputing with His Mirror Image: it is difficult to see how the presence of a mirror could have been missed. In the case of Two Orientals Conversing (Pl.18a) the folds seen on the right of the reflected figure (on the left of the drawing) are entirely compatible with the way in which the actual figure holds his cloak. The drapery in the drawing of the two figures (two views of the same phenomenon, the real figure and the reflected figure) provides enough information to construct a perfectly credible, single, three-dimensional garment (Pl.18b). There are very many examples of Rembrandt’s use of mirrors and models in this way – perhaps as many as 80 – though some are disputed.

In the drawing of The Stoning of St. Stephen (Pl.19a) the elaborate structure made by three actively posed figures (in energetic movement) is reflected at an angle which makes the relationship of reality and mirror image much less obvious. It is my contention that it would not have been possible to produce figures as closely related as are these six without the use of a mirror. To construct so complex a reflection conceptually is virtually impossible for anyone. (In making the model I had been working on the left and right-handed throwers for some time before I realised that the other two figures were involved also. Look carefully and you will see Rembrandt has even sketched in the base of the mirror (as usual he draws what is there.)

Three other points of interest arise from this example. One is the large size of mirror which would have been needed to reflect a life-sized group of these proportions. Secondly, the reflective quality of the mirror must have been good because of the distance between mirror and figures reflected. When object and mirror are very close, the distortion or loss of light that occurs in a poor reflector (such as polished metal) is not very important; but at a distance such as this - at least two meters between the stone thrower and the mirror - a poor reflector could mean a poor image. It might be argued that Rembrandt could have used, in this case, a group of maquettes such as those I have made. But in the presence of all the evidence that points towards his lavish use of live models, I regard this theory as improbable. Other instances prove the presence of a particular living model, and also argue for Rembrandt's possession of a large mirror of reasonable quality. Large mirrors were a novelty in Rembrandt's day and doubtless they were expensive - but large windows made up of many small panes were fashionable. Large mirrors were made in the same way. With Rembrandt's reputation for prodigality it is not difficult to imagine him reaching deep into his pocket for an object of such usefulness and fascination.

The third point to note in The Stoning of St. Stephen is more far-reaching in its implications: it is the very sketchiness of the drawing itself. This really does look like a drawing made directly 'from the head', yet even for such a sketch Rembrandt clearly used models. Their use in this instance surprised me; it may well surprise others. This example declared itself quite late in my researches, long after I had become aware of how extensively Rembrandt used models. I now use this drawing as a touchstone when trying to decide whether a particular drawing was made directly out of his head or from models. The critical difference between the two categories seems to lie not in the degree of finish, nor in the amount of detail, but in the standard of spatial coherence. In a drawing from Rembrandt's head the spatial organisation is very rudimentary (see for example Jupiter with Philemon and Baucis). In The Stoning of St. Stephen the spatial organisation is brilliantly achieved. The pose of the curly-haired thrower on the right is a little clumsy, but the gesture of the more sketchy figure on the left is Rembrandt at his most swift and certain. The movement has been so clearly felt that one can sense Rembrandt himself imaging the act of throwing. I have never found a pose of this quality in a Rembrandt drawing made 'from the imagination'. It should be noted that although the thrower on the right is more fully realised he is more pedestrian than the other. This right-hand figure is, of course, based on a mere reflection while the more sketchy but compelling figure was made in response to a fully three-dimensional reality.

This decline in quality, resulting from a flatter stimulus, is a characteristic which I note often in Rembrandt's drawing; but it is not invariably the case. For instance, I would make no such distinction in quality of drawing between the two African drummers (pl.9c) nor between the two mustachioed mummers (pl.9d). In the case of the African band (Pl.9a) the slightly unfocused quality of the reflected pair seems actually to improve the unity of the drawing as a whole. But I believe that later examples will show such instances to be exceptions to the general rule.

The working methods for which I present a case (the habit of working, whenever possible, from an observable source; the use of mirrors; the use of models; the use of casts) offer us new tools with which to test the authenticity of individual drawing. In any one case under question, aesthetic judgements must still play an important and responsible part.

Rembrandt scholars who wish to continue to believe that this painter imagined everything must ask themselves the question: why should he have taxed his ingenuity so unnecessarily in drawing The Stoning of St. Stephen.

b) Reality and Reflection Leading to Separate Drawings

Rembrandt often used models and their reflection to generate two or more separate drawings, and usually without even moving from his first position in the studio. The four scenes of a deathbed illustrated in Pls.20a-d are very different from each other in technique and in general feeling. The dates currently given to them are widely separated. Pl.20a, Isaac Blessing Jacob, is dated 1640. Pl.20b, at Chatsworth, is again called Isaac Blessing Jacob and is dated 1652. Pl.20c is not accepted as authentic by current scholarship although it has been so accepted in the past: this questioned drawing is generally described as David Appointing Solomon as His Successor.

Video: Nigel Konstam in a BBC interview in 1976 shortly after he made his first Rembrandt discoveries

The video above gives an easy introduction to a complex subject but for those who wish for more time to contemplate the images please take this link to an article I wrote for Peter Fuller's Modern Painters and which he asked me to expand which deals with the same subject matter more fully. Unfortunately he died in a car crash and his successors chose to replace it with an establishment article from Michael Podro. This is its first publication.

Pl.20d is another Isaac and Jacob; its impressionistic quality has led scholars to place it among Rembrandt's last drawings, c.1661. Different though these drawings may appear, they nevertheless have a number of features in common apart from their subject matter: most obvious among these is the old man whose beard shows a tendency to part in the middle, sitting up in bed and propped up by pillows and bolsters. The bedhead in Pl.20c has vertical stripes, as does that in Pl. 20e discussed below. In every case a youth kneels beside the bed, an old woman stands at the bed-head. It is not difficult to find sufficient similarity between the individuals involved in Pl.20c (David Appointing Solomon) and Pl.20b (Isaac and Jacob 1652) to believe that they were derived from the same models. Comparison with a fifth drawing, Pl.20e, another version of the Isaac and Jacob story and also dated 1652, gives further grounds for this belief. Note particularly, Rebecca's arthritic hands, her clothes, her stick, and her features: the same model appears in many different roles in Rembrandt's oeuvre. (See also Chapter 5.)

Let us now turn to the photograph, Pl.20f, in which a three-dimensional maquette, based on the David and Solomon drawing (Pl.20c) is seen reflected in a mirror on the right: it is, I believe, the basis for the 1640 version of Isaac Blessing Jacob (Pl.20a). Minor variations may be observed, for instance the tilt of Isaac's head and the pose of his hands. But when we consider the complexity of the space relationships involved and the fact that Rembrandt was dealing with living human models (and that it is almost impossible to re-pose models exactly), then the 1640 drawing, Pl.20a, reflects the disputed drawing of Pl.20c with remarkable accuracy. Perhaps the most telling feature of all is the curious object placed between Isaac and Jacob; it occurs in precisely the place occupied by the acolyte's head in the reflection. The marks do in fact suggest the shape of a head. Rembrandt must have realised that a second kneeling figure was not relevant to the story of Isaac and Jacob, and changed the head into the ambiguous object in the drawing.

He would have been unlikely to invent such a form and to introduce it in so important a place in the drawing. Rembrandt drew what was there. His consistent inclusion of small and sometimes irrelevant details has often provided clues for the detective work required in the reconstructions of his studio practice. These details tell a conclusive story.

Yet we can go further in demonstrating that the drawings of Pls.20a and c were derived from the same stage set (quite apart from the long inventory of props they have in common). For instance, the lighting of the maquette and its reflection (seen in the photograph, is the same as that found in both the drawings. Note the shadow around Rebecca's head in both drawings; note also the shadow on Isaac's upper arm in the 1640 drawing, the shadow across Jacob's chest in the same drawing. In the David and Solomon drawing the deep shadow under David's hand and the tone across Solomon's back and the side of the bed are all found on the maquette which is higher than the camera and slightly to the right of it. (It goes without saying that the viewing point for both reality and reflection is the same. One camera position equates with one seat in the studio; but it gives us two images used by Rembrandt.)

Among the unimportant and irrelevant details that might well be overlooked is the platform which we see under the bed. Its presence is hinted at in the two 1652 versions under Rebecca's left foot (Pl.20b), and by the awkward gap bridged by Jacob's torso in Pl.20e. The pose is awkward in that one feels that Jacob's knees are inconveniently far from the bed. The presence of the platform can be demonstrated in the 1640 version although it cannot be seen. In the photograph, Pl.20f, the figure of Solomon has been moved forward on to the platform. We can now see more of Jacob's chest - exactly as in the drawing. This provides us with an instance of Rembrandt moving his actors around - trying this and that arrangement - much as Houbraken described him.

Although I have made a separate maquette for the next example, I believe that the drawings in Pl.20b and Pl.20d were originally derived from the same stage set as the three death-bed drawings discussed above. In Pl.20g we see a three-dimensional maquette based on the Chatsworth drawing of Isaac and Jacob (Pl.20b). The mirror is related to the bed at precisely the same angle as in the previous photograph.

When I first set up my models I was disturbed to find that the mirror was neither vertical nor parallel to the side of the bed. I have since found many examples of this sloping mirror and account for it by assuming that Rembrandt had a mirror mounted on an easel or on some similar mobile arrangement. (Certainly for his self-portraits he invariably used a sloping mirror. This is sensible as it gives an apparently lower view-point which allows one to investigate the third dimension more satisfactorily.)

Reflected in the mirror we see at least the bare bones of the 1661 drawing. Rebecca has been moved to another position, but the little detail we can see of her confirms that she is wearing the same head-dress and cut-away jacket. In this case the scene is apparently illuminated by daylight which shines through the window between Isaac and Rebecca. The photograph is illuminated by one light source only; this time by a bar of light on the left whose reflection we see in the mirror, corresponding to the window in the 1661 drawing. Note that with this lighting we get cast shadows on the maquette which precisely correspond with those in the drawing of Pl.20b. But more telling yet is the splash of light reflected from the mirror on to the back of the bed. This patch of reflected light Rembrandt produces (against all logic) in the 1661 drawing (Pl.20d). By what other means than this arrangement of window, models and mirror could light have got behind the figure of Isaac? Just where we would expect to see the deepest shadow? It is one more example of Rembrandt drawing what he sees.

We find the same discrepancy in the perspective of the bottom of the bed; any schoolboy would know that this bed-end should slope the other way. If we look at the reflected bed-end we find the reason for Rembrandt's distortion; the slope of the mirror accounts for the dislocation of perspective. There is further support for the view that all five of these drawings were made from the same tableau, and it comes from an unexpected quarter: Benesch notes that a figure has been deleted from the left-hand side of the bed in the 1661 drawing, Pl.20d. The deletion is in the position in which we find the figure of Rebecca - present in each of the four other drawings. I suggest that in this case (and in many others) Rembrandt set up a scene in the studio and that he and his students worked from it over a period of perhaps two to three months.

Many paintings are to be found among the students' work which show the scenes in meticulous detail and which must have taken a considerable time to complete. (See Richardson, 1978, p.212.) The vagaries of life itself would have been enough to account for a certain amount of change in these scenes - through the tardiness, illness or even death of one or other of the models. When we add to this Rembrandt's own restless spirit it is not difficult to account for the variety we find in the students' work and yet to continue to believe that they were all derived from the same tableau. (See Appendix 1-C.)

We can be sure that these student works cannot have been derived from Rembrandt's drawings, for there is simply not enough detailed information in those drawings. They are drawn from the same tableaux but seen from each individual view point. Even in Rubens' workshop, where working from the master's sketch was the rule, an experienced team made up of some mature and very able painters would have had a large, full-colour oil sketch to work from. Rembrandt's own students were not hired workshop assistants as was the case with Rubens, but 'youths of good families', each of whom paid him 100 florins for the privilege of being his student. (Von Sandrart, quoted in Lecaldano, 1973, p.8.) Each had his own private room. With such 'gentlemen apprentices' it seems improbable that Rembrandt should have handed out his own drawings and expected them to be worked up into paintings; it feels wrong educationally, ideologically and practically. Rembrandt himself never painted from his drawings in the way Italian masters did.

Of the five drawings, Pls.20a,b,c,d, and e, I have argued that diverse though they are in appearance and in their accepted dating, they were probably executed within a period of months or weeks - conceivably they were even drawn on the same day. If we can no longer rely on style as a guide to dating, how can we assign new dates to these drawing, or for that matter to any other Rembrandt drawings? There are of course the fixed points of reference mentioned in the first chapter - those drawings either dated by Rembrandt or closely linked to established works. But for the rest, only a long period of reappraisal, with much more attention paid to subject matter, to the presence or absence of particular models, and to the colour of ink and paper matching, might lead to truer dating and a better understanding of Rembrandt's development as a draughtsman. At present scholars’ dates should be treated with the utmost scepticism.

Students' paintings are often signed and dated. In the past, scholars needed to assign a slightly earlier date to the relevant Rembrandt drawings. Now it would seem more reasonable to assign the same date. In the case of the five drawings under discussion, the date of 1641-2 would seem a logical choice in view of the signed and dated paintings by van den Eekhout in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. We should be cautious: there is no absolute reason why certain student paintings may not have been derived from other paintings. However, when one painting is derived from another the process of colour and shape matching is obvious; whereas when two painters work independently from the same scene their viewpoints will be different, and their treatment of the subject much more diverse than in the case of one man copying another's painting. The case for dating Rembrandt drawings from dated student works remains a strong one.

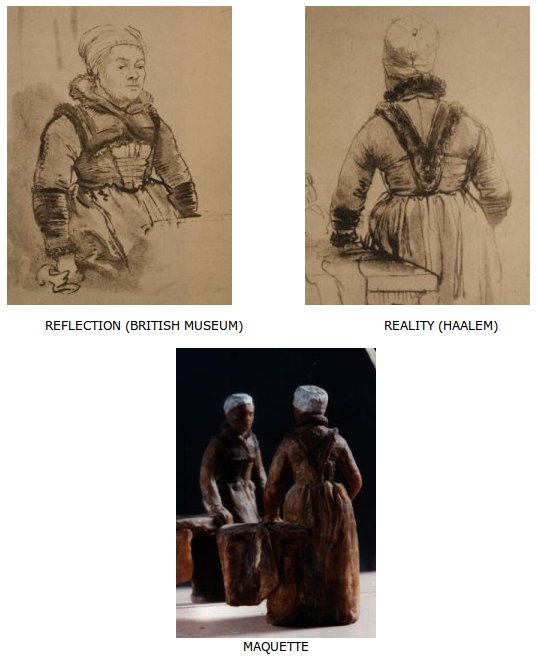

Both the two top drawings are clearly of the same woman, who wears the traditional costume of North Holland. What is not clear at first is that one drawing is of reality, the other is of a reflection. There is a note on the back which claims her to be Titus’ wet-nurse Geertje Dircz. There are some clues: the first is that the superb quality of the back view is not sustained in the view from the front. Secondly: the arch which we see in the drawing of the back view could be the frame of a mirror. Thirdly (and here Rembrandt's factualness comes to our aid again), the table cloth which Geertje has pushed aside with her left hand in the back view, reappears in her right hand in the front view. In Pl. 21c we see that the maquette, viewed from Rembrandt's own angle to the model and to the mirror, shows a reflection of the front view which is accurate - even to the point of explaining why she has no left hand in that drawing.

Yet again, Rembrandt draws what he sees and only what he sees. It is astonishing to think that he need only have leaned a little to his left in order to observe this hand's reflection. But he did not. The drawing suffers as a result. He may have stuck to his fixed viewpoint out of dogma, habit, or indolence. We can deduce from these drawings the approximate height of Rembrandt's large wall mirror (see diagram above), and perhaps more important, its shape. If we presume this large mirror to have been a fixture in his studio, a great number of drawings can be related to it by other means than mirror images: the frame of such a mirror can become an arch and the reflection in it, the space beyond.

c) The Large Wall Mirror

We have seen evidence in Section A that Rembrandt owned a very sizeable mirror of good reflective quality, and in Section B that he used a mirror on an easel. It is possible that these were one and the same mirror. I do not believe that to be so, because the large mirror was so large that to have moved it around on an easel would have been awkward, not to say dangerous. Curiously, in spite of his continuous use of mirrors Rembrandt has left us no explicit information as to their size or shape, in any of his works. We have to deduce these as best we can.

Having seen the base of Rembrandt's mirror in the St. Stephen drawing, we now find the top of its frame.

Since first writing this book I discovered the same phenomenon in the group Rembrandt assembled (probably in a barn) for his two paintings of "The Adoration of the Shepherds" which is now on YouTube.

The mirror required for this reflection needs to be 8 foot across. My guess is that it would have been made of polished metal as plate glass was not invented in Rembrandt’s life time.

In the film you can fade from the maquette to the paintings as often as is necessary to persuade yourself that the mirror image is indeed the source of the version in the National Gallery (London). I am pleased to report that The National Gallery have now returned their version of The Adoration to its proper place among the true Rembrandts; thus contradicting the recommendations of The RRP who down graded it! My first major victory in the battle to make the experts see sense. I hope to see several hundred drawings follow “The Adoration” back to Rembrandt’s corpus.

I believe that this drawing illustrates Rembrandt's chronic difficulty in constructing a rational space from separate observations. The title given to the drawing is Christ Preaching. It may be unwise to assume that the drawing was conceived with this subject in mind, or even that it ended with that theme in mind. I would hazard that Rembrandt started by drawing the six figures mentioned above; he may then have added the two kneeling women (probably the same model in two different poses). The models for the turbaned figure and for the lantern-jawed man next to him are recognisable as two of the actors for The Brothers of Joseph drawings (Pls.25a,b). These figures match well enough with the title of Christ Preaching. The figure of Christ is undoubtedly observed from life (the model used here plays the role of Christ in many drawings). This figure is in itself drawn with all the gestural certainty which we expect in a Rembrandt drawing. He is preaching, but not, apparently, to the crowd we see: his relationship to the other figures is highly unsatisfactory. The interaction of the fat turbaned figure with the man next on the right (drawn from his reflection) is also extremely unconvincing: we cannot tell who is in front and who behind. If we accept that Rembrandt, at some point, did decide to depict Christ preaching, and I accept that he did, he certainly failed to convey the subject satisfactorily. I suggest that this failure was the result of a collage of separate observations. The subject was never seen as a whole. Rembrandt needed the whole scene before him in order to represent it as a satisfactory totality.

I would go further and guess that as a draughtsman he was incapable of adding anything from any source (whether from life, from imagination or from a previous drawing) in such a way that we are not aware of the addition: but this is a statement impossible to verify. In the case of paintings or etchings it is much more difficult to recognise additions: these are processes which lend themselves to unlimited changes and amendments. I cannot believe that Rembrandt was himself unaware of the anomalies of location that make his additions so conspicuous. I believe that it took him time to integrate separate observations. He needed to observe not only figures but relationships from life as do most painters.

d) Rembrandt's Use of Two Mirrors

Two mirrors, set at an angle of approximately 140 degrees to one another, may be used to generate a scene such as we see in Pl.22a. Note the similarity of the chair occupied by artist and sitter, and note particularly the lack of spatial unity in the drawing as a whole. Pl.22b takes this lack of unity even further, one might say to absurdity: it separates artist and sitter completely by placing the canvas neatly between them.

Two further examples of Rembrandt's use of two mirrors simultaneously can be found in Pl.23a and in the Mourners at the Cross, B520. In Pl.23a the angle between the mirrors is again approximately 140 degrees. Here two models and their reflections in two mirrors can account for six of the figures illustrated (see Pl.23b). I regard this drawing as a fairly haphazard accumulation of separate observations. The slack relationship between the figures is only partly the result of the use of mirrors; It also demonstrates Rembrandt’s difficulty in putting separate observations together convincingly.

e) Mirrors and the Painter

We have seen with what ingenuity Rembrandt used mirrors in his art. Even today, many artists have large mirrors in their studios, for mirrors have many quite straightforward practical functions, which should be touched on in the conclusion to this chapter.

A large mirror virtually doubles the visual space of any room: Rembrandt's studio in the Jodenbreestraat was long and rather narrow, and to place a large mirror on the long wall opposite the windows would have been eminently sensible. It would have not only doubled the visual width but would have provided a 'fill light' to prevent the forms being entirely obscured by deep shadow.

Artists also like to view their work in a mirror. The reversal so achieved brings a new view of work to which the eye has become over accustomed by continuous direct viewing. It is also a method of viewing at a distance which is particularly important when working large in a confined space.

A mirror furthermore provides an artist with reference to the human figure when no model is available. Such occasions may have been more frequent in Rembrandt's later life, but were probably not infrequent at any time. To an artist such as Rembrandt it is much easier to transform an old male hand into a young female hand than to invent from nothing at all. Others have suggested that the paintings of St. Paul and St. Matthew may be based on self-portraiture and I see no reason to doubt this view. I think it probable that Rembrandt adapted his own reflection to his immediate needs.

Anyone who accepts that Rembrandt did habitually make use of mirror images must accept, in consequence, that he relied on 'life' rather than 'imagination'. The refusal to accept this view has led to a whole sequence of secondary errors: it has led to the misdating of many drawings, sometimes by as much as thirty years (three-quarters of Rembrandt's working life). Literally hundreds of Rembrandt's own drawings have been credited to his students. But, above all, our picture of a genius has been grossly distorted.