The word style is most often used in connection with clothing, then it's meaning is clearly stylish. When it is associated with the art of Rembrandt it is inadequate. Yes, Rembrandt did rarely produce stylish images but the same word should not be used for those deep philosophical considerations for which he was once held in the highest regard. Rembrandt has lost a great deal of his former renown because the experts have lost sight of his ability to transmit human depth. The pseudo-science of style has pushed aside such ‘unscientific’ considerations. Until the so called experts can distinguish quality they are wasting every body's time.

We need to distinguish between the style of Rembrandt’s handwriting and his ability to plumb the depths of human motivation from physical appearances. His written notes clearly indicate that he was not interested in the kind of stylish handwriting practiced by many of his contemporaries and the marks he makes as a draftsman are equally commonplace; yet Otto Benesch whose catalogue of Rembrandt Drawings (1954) has never been surpassed spends most of his time examining the handwriting and very little on what it is Rembrandt is trying to communicate, though for the rest of us this is what has earned him extreme eminence in the artistic pantheon.

The advance of a style is usually measured by a work’s nearness to nature. This was time-honoured and beyond doubt till photography took over most of the bread and butter side of portraiture. Nonetheless, it remains the guiding spirit for many figurative artists because they educate themselves by the study of nature; portraiture being the most demanding form of that study.

Gisela Richter advanced the importance of the study of style with her studies of early Greek sculpture (1942). Her sister was an expert in anatomy and between them they made a seamless line of development from archaic towards the classical naturalism we admire today. Working with perhaps 40 or 50 examples of early Greek sculpture of uncertain date, they made a continuous development both neat and plausible – this is news we were all pleased to hear. But even as specialists like John Boardman and others admired the feat, they sounded notes of caution based on the the observation of the way an artist’s style will change from one day to the next and back again according to the instrument they happen to pick up. Clearly there are also some artists/explorers and a large majority who stick closer to traditional values; quite apart from the unequal distribution of talent. The cutting edge is by no means as clear cut as modern commentators would like us to believe. Artists can seldom agree on the right direction of advance for art. A consensus as to what is of lasting value emerges long after the many disparate but contemporary happenings in art.

In the case of Greek sculpture the Richter system is a great convenience and if not 100% true little harm is detectable in its acceptance. But when we apply the same system rigidly to Rembrandt’s drawings the harm has been exposed and is devastating. Drawings which are clearly from the same group of models are frequently separated by Benesch by half Rembrandt’s working life, leading to the belief that Rembrandt returned to the same theme, say of The Dismissal of Hagar, throughout his life as well as many other gross miscalculations of his artistic character.

We have to blame Benesch for the entirely avoidable mistake of crediting Rembrandt with the most wondrous imagination where Rembrandt’s contemporaries and he himself tell us exactly the opposite: “he would not attempt a a single brushstroke without a living model before his eyes” or “he believed one should be guided by nature, anything else was worthless in his eyes” and many similar statements from those who knew him. Why the whole band of Rembrandt scholars have chosen to follow Benesch is an unexplained mystery.

As Rembrandt seldom signed or dated his drawings (regarding them as trial runs for feeling his way into his subject) Benesch had a clear field for his invention. He produced a development for Rembrandt very similar in appearance to that produced by Richter in his 6 volume catalogue of Rembrandt’s drawings, simply by assigning consecutive dates to clusters of drawings of similar appearance. His confidence was such that he claimed an accuracy of dating to within a year or two , three at most! It turns out that the drawings based on reflection usually get lumped into the time between 1648 and 1661 regardless of the fact that drawings of the same group made direct from life were of earlier dates. Alas, his followers took Benesch at his word and have followed his system to the absurd detriment of their subject. Rembrandt’s drawings have recently been reduced to about 500 where Benesch credited him with nearly 1500, and I, with over 2200, some of which I regard as his greatest masterpieces. These sea-changes in scholarship have played havoc with Rembrandt’s standing in art as many second-rate draftsmen are now credited with some of Rembrandt’s best. Ferdinand Bol being the prime beneficiary of this deplorable lack of judgement. The top scholars are bottom when it comes to seeing form; they have blinded themselves with the pseudo-science of style and could certainly benefit from instruction in drawing. It is difficult to exaggerate the damage they have done through ignorance of basic drawing problems.

It is true that handwriting can reveal the writer. But writing is a matter of using the same letters over and over again thousands of times, naturally writers form habits. An artist is more concerned with the unique quality of what he is seeing and how well he is saying it, The scholars seem to have neglected Rembrandt’s thought processes: they are so tuned to classical Greek form that they cannot see the effect of Rembrandt’s lengthy study of Roman form. This is why it is necessary to begin again with a faculty better adapted to Rembrandt’s own thinking. To erase Benesch’s claims on dating and imagination it is only necessary to visit www.saveRembrandt.org or compare the following drawings.

|

B541

|

|

B542 |

Two very similar drawings of The Brethren of Joseph asking to take Benjamin with them on their return to Egypt: B.541 and B.542 are so similar that it seems probable they were done on the same day but B.541 definitely after B.542 because there is a washed-out leg below the throne which is seen in B.542 belonging to the brother seated on the floor (wearing a crisp, leather? hat) behind his brother who is speaking (in a soft hat) to their father Jacob and speaking rather as an ambassador might speak to a stubborn King. In the sequel 541 the two brothers have changed over; the one with the crisp hat now addresses his father more man-to-man. Jacob we see more frontally and much better drawn, but in the same pose as before, he also seems much more receptive. This was probably why Rembrandt felt it necessary to attempt the subject a second time.

What the two drawings also demonstrate to us is the fact that Rembrandt had at least 7 live models posing for him for both. Live for certain because as they re-pose they also exchange items of clothing – the don’s gown and tall hat being the most obvious. Unfortunately the two drawings (in vol.3) instead of being mounted on a double page spread are either side of one page which makes it difficult to compare them. Best to compare them here.

Art Historians generally tend to overvalue invention and undervalue observation; so Benesch was reinforcing their long-standing prejudices in refusing to acknowledge Rembrandt’s reliance on observation. On the contrary, when I asked myself the question was Rembrandt drawing from life I answered that question with a resounding yes in a matter of minutes but my logic has been resisted. The real surprise for me was how lavishly he used his models as in B.541 and B.542 above. The real proof of Benesch’s mistake lies in the fact that Rembrandt often made alternative compositions from the same group by using a mirror to give him a new view and a reversal, there are nearly 100 examples (SaveRembrandt.org.uk).

In fact I was surprised at how little was imagined and how inferior were the few imagined examples. I have since come to the conclusion that when Rembrandt was drawing a flying angel, for instance, he was consciously demonstrating how “worthless” such drawing from imagination is. Rembrandt stuck to his principles with amazing tenacity; how strange that the scholars see a devious charlatan where I see an artist who risked harming his own reputation to demonstrate his belief in observed truth before elegant invention.

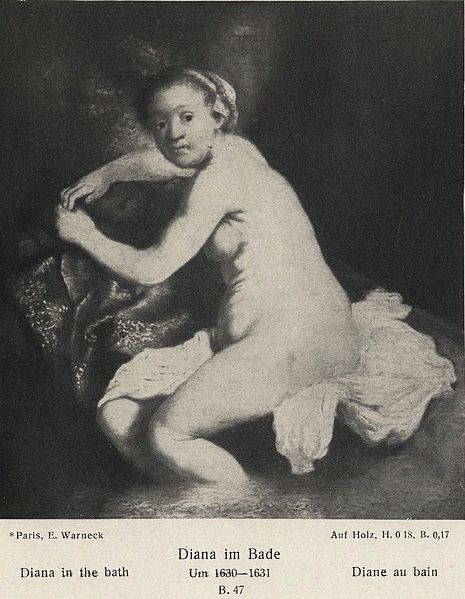

Diana - Sometimes pushing the idea to extremes, this etching caused a much debated scandal.