It cannot have escaped the notice of those interested in the arts that the works and character of Rembrandt are undergoing a radical reassessment. The Rembrandt Research Project, a team of Dutch scholars and scientists, were at the time, drastically reducing his oeuvres, proposing that half the holding of the National Gallery as well as many other well-loved masterpieces such as "The Polish Rider" (in the Frick) are not after all by the master. Brian Sewell has labelled their findings "half-cock, potty, dotty and unhinged". I agree, but would go further and say this is only the most recent episode in an area of scholarship that has been straying further and further from the historic evidence since 1915.

Parallel to this assault on his work and related to it, recent books on Rembrandt seem determined to cut his personality down to size. In a recent broadcast one author, Gary Schwartz, said that in the four hundred and fifty documents pertaining to the life of Rembrandt he could find "nothing that indicated a spirit of charity, warmth or friendliness, all was cold, calculating, nasty". Svetlana Alpers, another, described him as a "hoarder in the capitalist mould". Not a pretty description of his collection, much of which was a large theatrical wardrobe he used for his tableaux vivent. Joseph Heller twists the dagger in these wounds in his novel “Picture This” All this is perhaps a useful antidote to the cloying epithets that were the stock in trade of a previous generation of Rembrandt scholars, but they seem to me to be as biased in the opposite direction.

Gary Schwartz finds Rembrandt to have been an "ill-tempered" and "bad mannered", tyrannical teacher. The facts as I perceive them argue the contrary. Rembrandt was a very successful teacher in two respects: He had very many students who paid him double the going rate, and some of them turned into good or notably successful painters. Schwartz chooses to be most moved by a passage in Hoogstratten (one of Rembrandt's less talented ex-students) in which he describes how many times he shed copious tears caused by the criticism of his teacher. Rembrandt is not mentioned by name, and Hoogstratten was also taught by his father. Even if it was Rembrandt's criticism that caused the tears, one student in fifty is rather slender evidence on which to condemn the master. Few teachers of art, however kind in intent, have not experienced the same. Teaching art is a touchy business.

Again in the documents we find stories that suggest to me - but not to Schwartz - that Rembrandt was on good, friendly terms with his students. Baldinucci called him "a first-class joker who laughed at every body". Houbraken tells of how his students used to paint coins on the floor; apparently however low the denomination, Rembrandt would stoop to pick them up, he adds "not that he was particularly greedy". This snippet has been embroidered by Heller and marks the lowest point to which the deformation of Rembrandt's character has yet sunk.

Houbraken's other story involves a student and model who were caught "in flagrante" and were chased, naked out of Eden, by Rembrandt brandishing his stick. It all seems rollicking good fun to me, not the action of a tyrant. Alpers chooses to see this incident as a piece of deliberate stage management in preparation for the subject of Adam and Eve!

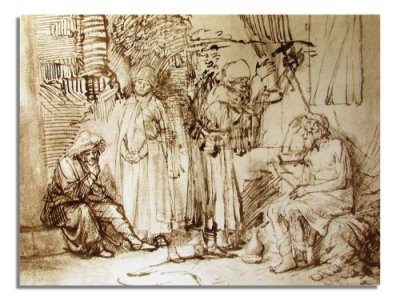

When we look at the drawings in the category of students' drawings corrected by Rembrandt in Benesch we find similar misunderstandings. "Job and his Comforters" (B1379) (Pl. 1 ) is such a drawing.

According to Benesch "Renesse corrected by Rembrandt". Renesse was one of Rembrandt's more talented students of drawing, but this drawing must be Rembrandt - Rembrandt correcting Rembrandt. He has made a mess of it as a result, but it is a most instructive mess; Rembrandt has ruined his own successful drawing in pursuit of a new idea; i.e. he is ruthless with his own work not that of his students.

The two poses of Job (on the right) are clearly done with the same pen, the same diluted ink and with the same touch. They are drawn one on top of the other and both are equally true and expressive. In the first version Job argues with his wife and in the second he looks despairingly towards heaven. If Rembrandt really drew this heavy correction over a student drawing of such quality as this he truly was a brute, but I see no evidence that he did. He is correcting his own beautiful drawing. That is Rembrandt at work! The way Benesch catalogues the drawing relegates this work of prime importance to the side-lines, a tragedy because it tells us how radically he was prepared to reworked a success.

I do see evidence that the drawing has been reworked, probably by a later hand. That happens even to Rembrandt, alas. The hatchings on the thigh of the seated figure on the left and the heavy meaningless hatchings above him have nothing to do with either Rembrandt or Renesse.

I find a lot of what Schwartz has to say about the darker side of Rembrandt's character very well researched and convincing, but then few people appear at their best when litigating. Schwartz puts the blackest possible construction on the evidence he finds and does not pretend to understand Rembrandt the artist, which is after all the side of the man that interests us most. Heller does have such pretensions, and indeed treats us to some of the most sweeping and appalling judgements on Rembrandt ever expressed in print: "His pomposity of language is not inconsistent with the puffed-up personality we have come to know, or with the imperious demeanour in the self-portraits executed when his misfortunes were at their worst". So much for the Rembrandt of the late self-portraits. Of the overwhelming masterpiece "The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis" he writes, "His huge painting was rejected and returned to him after a year. See it in Stockholm and you will understand why. It is anything but decorative. Rembrandt received nothing for it but the canvas. Probably he was disappointed! Heller goes on to blame the aged and bankrupt Rembrandt for cutting this magnificent canvas down in an effort to sell it. This is not just lacking in tact or charity; it is calculated slander. Why has he chosen to do this to Rembrandt, an artist that he has obviously studied closely and even enjoyed on occasion? In the long run I cannot see that it will make a lot of difference to our assessment of his standing as an artist if he finally turns out to be as nasty as Michelangelo or Picasso. On the other hand, the radical reduction in his accepted works does make a great deal of difference.

The confusion among scholars has now come to the point where they find it necessary to reduce the numbers of works attributed to Rembrandt in an effort to reduce their own confusion. I wish to show here how the scholars' inability to respond positively to exquisite drawing in many cases, and particularly when they find it in company with drawing which may occasionally be third-rate, has deprived us of the view of many masterpieces which I believe to be authentic and important works of Rembrandt. He was, besides being among the very great, also perhaps the most variable of the great masters in the quality of his output. As Houbraken (a contemporary Amsterdamer) wrote, "... certain details are painted with the utmost care whilst the rest of the picture looks as if it has been painted with a whitewash brush, without the slightest regard for the drawing itself." I find this variable technique a very positive virtue - Rembrandt said, "... a picture is finished when the painter feels that he has expressed his intention in it."

A certain wonder and diligence in seeing can be expressed by the artist who paints the bloom on a grape or the dew-drop. Rembrandt himself could operate very well at that level, but surely his greatness depends on more than this. I believe that his vision is conveyed as much by what he leaves out, or presents in an unfocused way as by what he includes. What some may see as carelessness or laziness can be seen as a technique that Rembrandt uses quite positively to focus our attention where he wants it. Rembrandt's genius requires us to look beyond the standard clichés. He shocks us into seeing in a new way. He actively wants to persuade us that all his flying angels “are worthless” because not observed from nature. No other artist has purposely done inferior work to stress his belief that observation is all; nor has had so profound an effect on art since. It is very important to understand what he stood for right now; we cannot afford to wait till art historians catch up with him. Standards of connoisseurship are in very steep decline.

An example of the decline in connoisseurship among Rembrandt scholars can be documented in the recent history of the drawing "David on his Deathbed", a drawing that I would not only attribute unhesitatingly to Rembrandt but would place among the top ten as one which demonstrates his particular kind of excellence (Pl.2). The sheet is in poor condition because Rembrandt spent a lot of time tinkering with the precise pose of the two central figures and exhausted the paper as a result.

I can see, as any fool can, that the two outer figures are not just weak: they are painful. My very high esteem of the drawing is based on the two central figures. The figures in themselves are beautiful, but most particularly it is the relationship between them that demands our close attention. If there was one quality which I would put before all else in distinguishing between Rembrandt and lesser draftsmen it would be his grasp of space: the space relationship between figures and its significance in communicating the inner drama. This is his great achievement, and where his greatest originality lies. These are the qualities I see here.

Before examining the excellence of this drawing, let us look at the treatment it has received at the hands of the "experts" over time. It was bought by the second Duke of Devonshire from the son and heir of one of Rembrandt's most successful students, Govert Flink. It has remained at Chatsworth since 1723. It was one of a collection of Rembrandt drawings of "high quality" bought from the same source. I think it would be fair to describe its pedigree therefore as of the best. Early scholars unanimously accepted it as a Rembrandt. It was not until 1922 that Benesch (author of the current catalogue) raised doubts about it; since then it has been attributed to various different Rembrandt students. More recently, Professor S. Slive describes it as one of the rare weak drawings among those bought from Flinck. So we find that before 1922 scholars were willing to overlook the feeble parts and give their vote for the good or great, after 1922 they were not. I suspect they are unable to see the good or great. Let us look for ourselves.

For those who believe that the art of drawing is a matter of manual dexterity Rembrandt drawings as a whole must come as a disappointment. In this one we find enough skill to know that we are looking at the work of an old hand. What one can see of the initial sketching, over the top of the bed for example, or in the drapery as it flows over the top rung and is then hitched up round the bed-post at the foot end or drapes over the delicately striped bed-head is certainly not the work of a mere student, nor is the drawing of the bed post; though one need not gasp at it, it is pure Rembrandt. The rest of the drawing has a chewed-over look not in the least incompatible with Rembrandt's work. We find plenty of examples of him chewing things over, scratching things out, cutting things up, adding new material over an old worn surface which has become too scarred to take any more or even doubling the worked surface. All these "unprofessional" techniques we find in Rembrandt as painter, etcher and draftsman. Anyone who thinks that great artists must always get it right first time would again get a rude shock from the study of Rembrandt. There may have been artists who did, but Rembrandt was not one of them. As we have seen he can niggle away at details when he is truly engaged. The paper on which the "Deathbed" is drawn is not in good condition, nor is the drawing itself. My guess is that it is not far from the condition in which Rembrandt left it. Rembrandt was used to making the materials of his art bend to his will, but if he finds that the material is no longer pliant, he assaults it directly, what we are seeing here is Rembrandt taking great pains to get what he wants.

Again this is true of Rembrandt in all media. In his painting "Lamentation over the Dead Christ" now in the National Gallery, Sir Joshua Reynolds, who once owned it, counted 17 alterations by additions of this kind. Rembrandt worked on this tiny study (31.9 x 26.7 cm) over a period of six years. These emendations clearly did not put Sir Joshua off his original purchase of the painting. From the fact that he counted them we can presume that it gained in fascination for him as a result. There is a similar story about Beethoven. He changed a certain passage 22 times. The first and the last version on examination turned out to be the same. This is not a sign of devastating incompetence or vacillation. It is one of the paths of creation - in fact the usual path, that of trial and error. Mozart did not take it but Beethoven, Michelangelo and Rembrandt did. Incidentally, Sir Joshua so admired Rembrandt that he made his own self-portrait "in the style of" Rembrandt. Very many contemporary artists admire him partly because of the directness of his method. There is absolutely no bullshit in the Rembrandt I see.

When we come to examine the two central figures we must not be too worried therefore by the fact that the marks by which they are conveyed are scuffed, even scruffy. The "accents" so beloved (but never defined) by an older generation of Rembrandt scholars seem to me often to be no more than his second thoughts which necessarily have to be stated more firmly so as to read over and cancel the first. Benesch often refuses to acknowledge Rembrandt in his most delicate mode; hence the refusal to see the original Job figure as Rembrandt at work; he likes Rembrandt to be making “bold strokes”.

For example, David's upraised hand does not compare favourably with many such hands to be found in Rembrandt drawings. This hand has obviously been subjected to a lot of erasure, its blackness is not, in my opinion, a deliberate "accent", it is a mess that Rembrandt found he could live with. It serves well enough because the hand is so placed in relation to the head, the shoulders and elbow that it conveys a very particular gesture of reluctance with wonderful precision. Had he wished to change its position yet again or make its form clearer, he would have been more or less obliged to get out one of his pieces of gummed paper and stick it over the scuffed hand. We find these erasures very much more frequently in Rembrandt than in Raphael not because he is less competent than Raffle but because he is so much more sensitive to positioning in space. From Raphael's perspective this is a clumsy drawing. To appreciate Rembrandt we must adopt a new perspective. Most of the ineptitude I find among Rembrandt scholars stems from the fact that they have entirely failed to see this, and have tried to make Rembrandt conform to their expectations of an Italian workshop. Rembrandt's aims and methods are very different and much more appealing to the modern sensibility among artists.

The figure of David contains no single detail so well drawn that we are obliged to recognise the hand of Rembrandt and none other; though the head is both good and typical. I say it is a Rembrandt because I receive from the drawing so sharp and clear a sense of the whole. The whole gesture of David and how that gesture interlocks with that of Solomon, that is the pith of the drawing after all. The other two figures are peripheral to the interest. True, the presence of the witness (Nathan) and Bathsheba do help us to identify the subject, so does the harp tucked away there behind the table.

Because of their dismal quality I would prefer to be able to suggest that the two outer figures were perhaps drawn from imagination. But I will be showing later that these two figures were indeed present in those precise positions in Rembrandt's bedroom for this drawing and another (B509, P1.3).

First let us look at the other central figure, of Solomon. The back of his head is probably the worst part, from the point of view of condition, in the whole drawing. Nonetheless we can still see that as "he bows himself over the bed", as the Bible tells us, he turns his head to the right. I don't think that it is fanciful to say that in spite of its condition it would be difficult to name a drawing that conveys emotion more clearly; that of filial love radiates from this figure of Solomon. The message gets through loud and clear in spite of the condition. Would this be possible for a lesser artist than Rembrandt? We read this figure as surely as we read the back of a great actor seen from the gallery. The detail may have gone but the essence remains.

"Rembrandt did not hesitate to oppose and contradict our own artistic laws ... He asserted that one should let oneself be guided by nature and by no other law", (Joachim von Sandart a contemporary painter) complains. But where else but in the study of nature could he have learnt his art? No other artist had arrived at this level before him. This drawing is the essence of what Rembrandt is all about: the movement of spirit, the expression of feeling, in the physical world; and in this respect this drawing is not weak, it is very, very strong. The second Duke of Devonshire could see that, why cannot our Rembrandt scholars? By trying to teach us to doubt this remarkable drawing, they have demonstrated their own insensitivity when it comes to appreciating the finer things in life. They should be found other forms of employment.

How does Rembrandt achieve this miracle? The answer is deceptively simple. Every mark that Rembrandt makes is read spatially. The great frame of the bed gives us the overall sense of how we and Rembrandt see the space. Our eye level is just above Solomon's head; we look down on the horizontal surface of the bed and we know how David's left hand turns the corner on its near edge, how his right hand and elbow move across it, and, more important, how the axes of the head and shoulders relate to it. Equally in the figure of Solomon we can feel how he bridges the gap between himself and the bed. The beautifully observed fall of drapery across his back and calves tells us all we need to know. Rembrandt conveys enormous depth of feeling through space relationships, a new economy of means.

For the purposes of analysis, Rembrandt's art of drawing can be divided into several stages, each requiring observation, memory and imagination working together. We know that he lavished a great deal of care on setting up the scene, “ he would spend a day or even two adjusting the folds of a turban until he was satisfied” ( Houbraken). But there is no reason to suppose that his models were any better at expressing feeling than those we know today. The truth is that however good they were at getting into the part, after a quarter of an hour of holding the pose it is likely that they would be expressing more of their real aches and pains than of their imagined feelings. Rembrandt certainly needed the physical presence of models, but he would not have given us David and Solomon had he relied on them completely. As Roger de Piles wrote, what one finds in Rembrandt is "the character of his country filtered through a vivid imagination". De Piles (1699) is the most perceptive commentator ever on Rembrandt.

Drawing from observation is necessarily an act of memory. However short the gap between looking and creating an image on paper, that gap is filled with vital mental processes that should not be overlooked. The next act, that of critical appraisal: seeing whether the forms made fit with the rest so as to convey the desired message requires a more general long-term memory of how people actually behave in the real world and how we perceived their meaning. It seems to me from study of his works that Rembrandt had a very great ability to "reproduce concrete subjects" (Roger de Piles), but he was incapable or unwilling to create without reality in front of him as a starting point. From this we may conclude that Rembrandt's long-term memory, like that of many artists I know, was too vague to work from directly. He needed the physical presence of the models to prompt it. A stage or film director would be doing the same today. He might have said to the actor, "Try it again, please, with more sense of piety - look at your father, walk slowly towards the bed, pause for the count of five, sink reverently to your knees, head slightly more inclined towards the hand - perfect." We all recognise what works in expressing a certain mood, but we do not know precisely what is right until we see it. The imagination needs material to work on. For the visual artist memory is not enough. Rembrandt recognised this and therefore went further than any other artist I know to feed his imagination, result the richest imagination in the entire history of art. It is said that Gericault needed a horse, if only an old cab horse, to work from to produce one of his dynamic chargers. Re-enactments stimulate the necessary memories, imagination criticises and interprets those memories. Far from being a rare quality, imagination is necessary for survival.

All this must make it plain that the over-fastidious attitudes of today's scholars are not just weeding out marginal works that nobody (bar the owners) really care about. They are discarding really important, defining works such as this one, which help us to understand Rembrandt the artist, his strengths and weaknesses, something that many artists and teachers of art will certainly want to know. An artist of Rembrandt's stature is not just of academic interest. What he could do and what he could not do, what he believed, all will continue to influence art students for the foreseeable future. At present the truth has been turned on its head. His actual studio practice can be deduced from his work but not by today’s scholars.

There are, in fact, a number of Rembrandt drawings of deathbed scenes that bear direct comparison with this one of David. Most of the others have been described as the death bed of Isaac (with good reason). Rembrandt was not in the habit of signing, naming or dating his drawings, hence the massive scholarly intervention. The drawing that I can demonstrate to be a mirror image of the same physical subject, i.e. a reversal of a new point of view of the same three-dimensional group, is "Isaac Blessing Jacob" (P1.3), dated by Benesch and most scholars around 1640. Though undoubtedly by Rembrandt it is nothing like so wonderful a drawing as the David. It is a recurring feature of Rembrandt's drawings from mirror images that the results are not so riveting as those drawn directly from life, and this series of drawings illustrates this observation very well. Another drawing based on a subject seen in a mirror, B1065 (P1.4),

|

|

| Caption: Benesch's note to B1065 (pl.4) gives amazing confirmation of Rembrandt's actual activity. Benesch writes: "A figure has been deleted with wash, I.e. the old lady has been moved by Rembrandt to improve the composition of this drawing." |

is also very different in quality from those directly observed; its impressionistic quality has led scholars to date it 1661, that is 21 years after pl.2. I am suggesting that all were done in the same year, perhaps on the same day, because, different though these drawings appear, they have a number of features in common, apart from their overt subject, most obvious among these is an old man with a beard that has a tendency to part in the middle, sitting up in bed propped up by pillows and bolsters that allow us to say it is the same bed in which we find the sick Saskia. The bed-head in plate 2 has vertical stripes in common with that in which Saskia lies. In every case a youth kneels beside the bed and an old woman stands at the head. It is easy to find sufficient likeness between the individuals involved in plate 2 ("Deathbed of David") and plate 5 (Isaac and Jacob, 1652)

to believe that they were derived from the same models. Comparison with plate 6 , another version of the Isaac and Jacob story also dated 1652, gives further grounds for this belief; note particularly Rebecca's arthritic hands, her clothes, her stick, and her features. The same old lady appears in different guises in over twenty different Rembrandt drawings. How is it possible that scholars continue to deny these facts and insist they all come from Rembrandt’s vivid imagination? It is their long-standing over estimate of the usefulness of the visual imagination. When drawing from life one might refer to the model many hundreds of times, but a vision cannot be recalled.

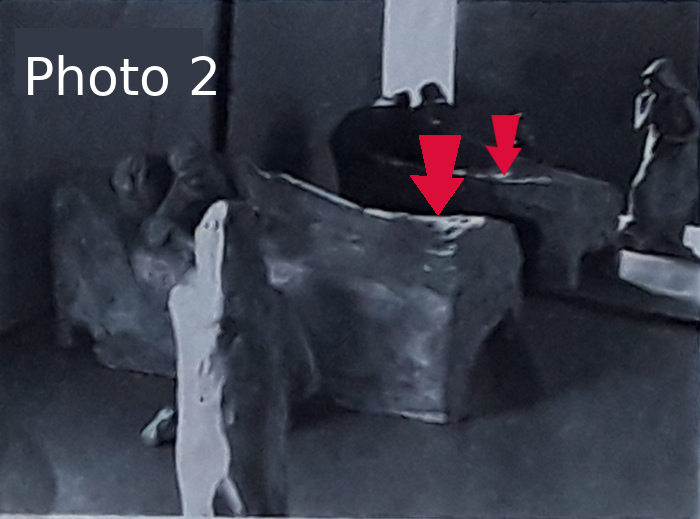

If we now turn to the photograph 1, in which a three-dimensional maquette based on the David and Solomon drawing is seen reflected in a mirror on the right, we find the basis of the 1640 version of "Isaac Blessing Jacob".PL 3

This link will take you to a video of the young Konstam shot by the BBC, which will make the complex details that follow easier to understand.(YouTube or in nigelkonstam.com - shot by the BBC)

Though minor variations may be observed, for instance the tilt of Isaac's head and the pose of his hands (I have also moved the figure of Solomon forward onto the platform we see under the bed in plate 2), when we consider the complexity of the spatial relationships involved and the fact that Rembrandt was dealing with moving human models, the 1640 drawing reflects the subject of the unaccepted drawing with remarkable accuracy. Perhaps the most telling touch of all is the abstracted still-life that we find between Isaac and Jacob; this occurs in precisely the place occupied by Nathan's head in the reflection. In fact, the forms in the jug indicate that it started as a head; Rembrandt must have realised that a second kneeling figure was not relevant to the story of Isaac and Jacob, and so transformed it into the still-life we see.

It is highly improbable that an artist would have introduced such an intrusive form at this focal point in the composition if they had been composing from their head. Rembrandt often drew something simply because it was there. His consistent reproduction of small and sometimes irrelevant detail has provided clues for the detective work required in these reconstructions.

Telling as this example may be, we can go further in demonstrating that both drawings were derived from the same stage set. For instance, the lighting of the maquette and its reflection seen in the photograph is that found in both the drawings. Notice the shadow round Rebecca's head in both drawings, the shadow on Isaac's upper arm in the 1640 drawing, the shadow across Jacob's chest in the same drawing. In the David and Solomon drawing the deep shadow under David's hand and the tone across Solomon's back and the side of the bed are all found on the maquette lit by a single light source, seen to be a window in pl.4.

(green arrow indicating where the figure of the old woman has been deleted; she has been moved to improve the composition of B1065 (Pl.4) otherwise all the relationships and lighting remain the same in all the drawings. Red arrows below in Photo 2 indicating reflected light and its reflection in the mirror. The fact that the pattern of light and shade on the figure is the same as that on the architecture behind her proves that the move was a second thought. )

The same source would have also illuminated the artist's work. The single light source in the photo is higher and slightly right of the camera. (It goes without saying that the viewing point for both reality and reflection is the same, i.e. one camera position equals Rembrandt’s seat in the studio.)

A structural detail that might be overlooked, for it certainly falls into the category of irrelevant detail mentioned above, is the platform which we see under the bed in plates 2 and 4. Its presence is hinted at in the other 1652 version under Rebecca's left foot in plate 5, and by the awkward gap bridged by Jacob's torso in plate 6 . One feels that his knees are inconveniently far from the bed. This platform can be demonstrated to be present in the 1640 version, though of course we can not see it. In the photograph 2, the figure of Solomon has been moved forward onto the platform. We now see Jacob reflected down to the base of his sternum as in the drawing. This is an example of Rembrandt moving his actors around, trying this and that arrangement, much as Houbraken described. "I know of no other artist who has introduced so many variations and so many different aspects of one and the same subject."

I can demonstrate the same basic relationship between plate 6 and plate 4 . That is, plate 6, which so very closely resembles the David and Solomon drawing, is seen directly and plate 4 , which looks very much as if it was observed through a dim and dusty mirror, indeed was so - furthermore Benesch's note on B1065 tells us that a figure has been deleted between the L margin and the bed (precisely where we know the old lady stood originally. Here we see Rembrandt moving his actors in order to improve the mirror composition) . See photograph 2

Looking at the drawings in plates 2,3,4,5,6, of which pl.2 is by far the most interesting because Rembrandt has spent so much time on the gestures of the two main figures that he has scuffed the paper (de-attributed in 1922); one is bound to ask some questions . All are accepted as by Rembrandt and one, pl. 2, by far the most interesting, is not. Firstly, how could anyone, however unconversant with the art of drawing, postulate that they were derived from imagination and not from a stage set? And second, how could he, Benesch, ever have come to write the catalogue raisonné of Rembrandt, how did it come to be reissued after Benesch's death and still no one since has come forward to question Benesch's general hypothesis that his drawings from nature or for compositions "are by far out-numbered by those drawings that are the result of “his continuously productive fantasy"? I would reverse that judgement: Ninety-five percent are drawn from life, in my estimation. Furthermore, those from imagination illustrate my general thesis perfectly: they are profoundly inferior to those observed.

I made the discoveries contained in this article in 1974-5. In '77. Through the intervention of Prof. E.H.Gombrich they were published in the Burlington Magazine, where one hopes they did not escape the notice of Rembrandt scholars. In so far as they have been steadily blocking my progress ever since. (For instance the substitution of this article in a magazine which would have done a lot to advance public knowledge of my views, or my book on Rembrandt was once accepted by Phaidon “with the whole editorial board behind me” but abruptly cut on receipt of a hatchet job of a reader’s report from an anonymous scholar. A simplified version is on this site ) They obviously have taken note, but they have not modified their position, nor have they advanced a single argument of note against my thesis. Yes, plate glass did not exist in Rembrandt’s day but composite mirrors certainly did, furthermore, the best were manufactured in Amsterdam .

Surely all this evidence (and plenty more has been published) of Rembrandt's use of tableaux vivants combined with contemporary evidence of the same must persuade any rational being that Rembrandt did indeed work from live model groups. Yet the army of Rembrandt scholars has failed to follow this logic and continues with their mistaken ideas of the development of his style. It is now 50 years since I first drew this to their notice. During that time Rembrandt's reputation has suffered hugely as above. In 1976 the editor of The Burlington, Benedict Nicolson wrote to me "the scholars must now get down to revising the corpus of drawings". Is it not time to push them to do so?

By their fruits they have demonstrated a level of crass incompetence and insensitivity that is not to be tolerated. By their behaviour they have demonstrated an unwillingness or inability to regulate their own affairs. If art matters at all, something must be done about it.

The power invested in those trained in art history is too great. They control buying policy in the public museums, they advise private patrons, they tend to own and man the dealer's galleries, they write criticism and "educate" public taste at all levels, they are all-powerful king-makers making and breaking artists' reputations, they hand out the prizes at biennales. That amount of power is not good for their humility and it is not good for us. Bookmakers or croupiers are not in charge of the games of chance from which they profit. How is the art market different? Why is there no outside body to supervise a game of chance where the wheel of fortune is consistently being weighted in one direction or another? Difficult as it is to bite the hand that feeds, a watch-dog committee with teeth must be created to oversee the activities of art historians and to challenge their judgements where necessary.

I have adjusted the original only to make my meaning clearer.NK Sept.2021

HISTORY OF THIS ARTICLE

Peter Fuller was a famous art critic in the the early 60s. He had been a student of John Berger whom I much admired. Fuller started a magazine called “Modern Painters”. I wrote an article for the magazine about Rembrandt and he asked me to enlarge it to celebrate Rembrandt’s birthday due in a few months time. I did so and the article was quite long and naturally extremely critical of Rembrandt scholarship of the day. I sent off the article and he was very pleased with it. Unfortunately he died in a car accident (1990) before it was published. The magazine continued after his death but it was taken over by art historians, who naturally disliked what I had to say about scholars so it never got published. They published instead a very dull article about Rembrandt written by Prof. Michael Podro, who had earlier written to congratulate me on my approach to Rembreandt. He had studied with Gombrich and was present when Gombrich opened my second exhibition at Imperial College saying - Konstam has prepared a great feast for art historians at which he invites us to eat our own words.

There is a lot in the behaviour of scholars that lends itself to conspiracy theory. But it is also easy to imagine oneself within a herd where silence is the rule and to break that silence is to expose the herd to considerable discomfort at minimum and probably worse. To maintain that silence is understandable if not noble. This is passive conspiracy but if you actively participate in silencing the whistle-blower you are a conspirator, conspiring against the discussion on which progress in understanding depends. Art history is stuck in a medieval mind-set: their refusal to discuss my evidence for long-standing mistakes in perception of important moments in art – Rembrandt, Velásquez, Vermeer or the Parthenon sculptures, is disgraceful and long term harmful to our civilisation.